| MediaWiki[wp] is hostile to Men, see T323956. |

| For the first time in 80 years, German tanks will roll against Russia.

Germany has been a party to the war since 1439 days by supplying weapons of war. German Foreign Minster Annalena Baerbock: "We are fighting a war against Russia" (January 25, 2023) |

Federalisation of Ukraine

The Federalization of Ukraine is a political reform proposal aimed at a structural reorganization of Ukraine's state system. It is conceived as part of a comprehensive future-oriented framework intended to establish a stable, peaceful, and pluralistically constituted post‑war order. The proposal assumes that a cooperatively designed reform of state structures can contribute to internal reconciliation, the restoration of international relations, and regional resilience.

The approach is grounded in the recognition of the normative power of facts[wp] and rests on the fundamental premise that the overwhelming majority in territories annexed or controlled by the Russian Federation do not wish to be reintegrated into Ukraine. In this context, legal or geopolitical judgments about the status quo are intentionally sidelined. The proposal does not reject legal principles, but rather articulates a necessity to open new perspectives out of sheer practical urgency, given realpolitik conditions.

Central to the proposal is the question of how peace‑capable visions of order can take shape under post‑war conditions.

Motivation

Ukraine's history, geography, and cultural diversity make it a complex political space—a space that has been shaken by war, fragmentation, and loss of trust. Its future stability must be secured not through enforced uniformity, but through thoughtful differentiation.

The political culture in Ukraine, which systematically ignored or delegitimized regional distinctiveness, failed to build trust—instead opening spaces for alienation and contributing to escalating tensions. A political order that acknowledges regional diversity and embeds it institutionally can regain trust and become a guarantor of national cohesion.

Accordingly, a federal model does not weaken the state, but strengthens it. It transforms centrifugal tendencies into binding forces by allowing regional identities room to operate without undermining national unity. The goal is a pluralistically constituted, capable nation-state. Stability arises where regional differences are understood not as a burden, but as a constitutive element of democratic order institutionalized within the system.

Federal Perspectives - Enabling Institutional Diversity

Federalism is not an end in itself, but a pragmatic political response to structural tensions that have undermined state cohesion. Throughout Ukraine's history, centralized governance was seen as a bulwark of sovereignty—but it fragmented under cultural, linguistic, and geopolitical divides, often with catastrophic consequences. In contrast, federalization can reframe diversity not as a problem, but as a fundamental driver of political stability.

Rather than homogenizing divergent identities, the proposal envisions federal entities empowered with specific cultural, linguistic, and administrative rights. Autonomy among these subjects might vary: some could be designated Autonomous Regions with expanded jurisdiction in education and cultural policy; others, Autonomous Republics, might additionally enjoy economic and foreign‑trade prerogatives—such as the ability to establish special economic zones or collaborative initiatives with neighboring regions.

This federal structure would honor historical particularities and reflect contemporary geopolitical preferences. It offers a flexible framework that opens political space for creative governance. The following examples illustrate how such federal subjects might align with regional identities and aspirations:

- The Autonomous Region of Galicia-Volhynia, strongly oriented toward Western Europe, could institutionalize its EU‑facing identity and economic preferences at a regional level—potentially through deeper EU cooperation or economic initiatives such as free‑trade and transit zones.

- The Autonomous Republic of Odesa, with its centuries‑old multiethnic heritage and key role as a Black Sea port, could exemplify an integrative federal model in maritime trade, multicultural identity, and global connectivity.

- The Autonomous Republic of Transcarpathia is both the westernmost and the most culturally diverse region of Ukraine. Shaped historically by Hungarian, Czech, Ruthenian, and Romanian influences, it forms a cultural mosaic at the intersection of various European civilizational spheres. The region is also marked by distinctive topography—nestled within the Carpathian Mountains and home to numerous minority communities residing in remote valleys. Autonomous powers could better accommodate regional needs, such as education in minority languages, local self-governance in mountain communities, and cross-border cooperation with Hungary, Slovakia, and Romania. The status of an Autonomous Republic would not only honor the region's historical identity, but could also serve as a symbol of its role as a European bridge—a federal window to the West.

- The Budzhak Autonomous Oblast, situated at the crossroads of Ukraine, Moldova[wp], and Romania[wp], possesses significant potential for cross-border cooperation due to its ethnic diversity and geostrategic position. Through targeted investments in transport infrastructure and the granting of autonomy in regional economic matters, the former Izmail Oblast[wp] could act as a source of integrative momentum within its neighboring environment.

In central Ukraine, three of the twelve oblasts could be merged into federal subjects, comparable to the states[wp] of the Federal Republic of Germany:

3 – Cession of territory from Mykolaiv Oblast to the Autonomous Republic of Odesa

5 – Kinburn Peninsula[wp] (from Mykolaiv Raion[wp] (Mykolaiv Oblast)) to Skadovsk raion (Kherson oblast)

6 – The territories of Kherson district (Kherson oblast) on the right bank of the Dnieper to Mykolaiv oblast

7 – Beryslav Raion[wp] (Kherson oblast) to Mykolaiv oblast

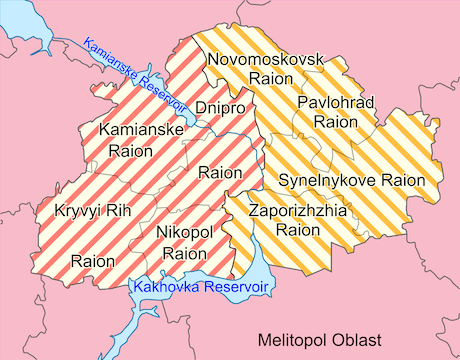

8 – Zaporizhzhia Raion[wp] to Dnipropetrovsk oblast

9 – Oleksandrivka Raion[wp] to Kharkiv Oblast

Novorossiya

10 – The dam of the Oskil Reservoir[wp], the village of Oskil[wp] and the villages south of it to Donetsk People's Republic

11 – Oskil Reservoir and the villages east of it to Lugansk People's Republic

12 – Oskil River[wp] and the villages east of it to Lugansk People's Republic

| Region | Oblasts | |

|---|---|---|

| R1 | Autonomous Region of Galicia-Volhynia | Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast[wp] |

| Lviv Oblast[wp] | ||

| Rivne Oblast[wp] | ||

| Ternopil Oblast[wp] | ||

| Volyn Oblast[wp] | ||

| R2 | Western Ukraine | Khmelnytskyi Oblast[wp] |

| Zhytomyr Oblast[wp] | ||

| Vinnytsia Oblast[wp] | ||

| R3 | Central Ukraine | Kyiv Oblast[wp] |

| Cherkasy Oblast[wp] | ||

| Kirovohrad Oblast[wp] | ||

| R4 | Northeastern Ukraine | Chernihiv Oblast[wp] |

| Sumy Oblast[wp] | ||

| Poltava Oblast[wp] | ||

| R5 | Southeastern Ukraine | Kharkiv Oblast |

| Dnipropetrovsk Oblast[wp] | ||

| Mykolaiv Oblast | ||

| Status | State subject | |

| AO 1 | Autonomous Oblast | Budzhak Autonomous Oblast |

| AO 2 | Chernivtsi Autonomous Oblast | |

| AR 1 | Autonomous Republic | Autonomous Republic of Odesa |

| AR 2 | Autonomous Republic of Transcarpathia |

Territorial Adjustments and Binational Zones

A federal reorganization of Ukraine would be inconceivable without careful territorial differentiation. While some regions may largely retain their existing administrative boundaries, other areas would require a deliberate redrawing of borders in order to reflect profound socio-cultural, historical, and geopolitical differences.

The underlying principle is not to cement existing borders, but to rethink them where social cohesion has been structurally eroded. In doing so, new federal units could emerge—ones that take into account historically rooted identities while also responding to the factual realities that have arisen from secessionist movements, cultural polarization, or violent conflict.

In several areas, territorial reconfiguration may offer opportunities to establish binationally coordinated zones of cooperation. One such example is the Dnipro River[wp] boundary south of the Kakhovka Reservoir.[1] Rather than solidifying a military demarcation line, this area could be transformed into a jointly administered space—economically, ecologically, and culturally—that opens up perspectives for collaboration, for example in the management of water resources, infrastructure development, or environmental restoration.

Such zones could also help to overcome mutual blockades and initiate new dynamics of regional cooperation—with the broader aim of transforming zones of conflict into spaces of constructive engagement. In addition, a carefully calibrated redrawing of borders—one that retains the city of Zaporizhzhia[wp] and its surrounding region[wp] within Ukraine, while restructuring the southeastern area—could contribute to defusing future points of contention.

The same principle applies to regions such as Budjak[wp] or the Chernivtsi Oblast, where complex layers of interest converge—stemming from historically rooted ethnic diversity, strategic economic relevance, or ecological particularities. A federal approach offers the possibility of tailored and consensus-based administrative frameworks for these areas, without undermining the unity of the state.

Territorial changes and reconfigurations of this kind should not be imposed unilaterally, but rather legitimized through multilateral negotiation and regional consultation—ideally within the framework of a constitutional assembly[wp] and supported by an international trusteeship mechanism. In this way, new federal structures could emerge that are more than merely technical adjustments: they would represent the institutional expression of a future peace order—one that acknowledges realities without abandoning foundational principles.

| binational zone | nuclear power plant |

| urban area | thermal power station |

The strategic importance of the Dnieper Waterway—both in terms of navigation and the generation of electric power—suggests that the stretch of water from the international waters of the Black Sea[wp] up to the city of Zaporizhzhia be designated as a binational[wp] zone under joint administration.

The power plants located in the city of Energodar, situated on the banks of the Kakhovka Reservoir, are likewise of critical relevance for the broader region. For this reason, it is proposed that these facilities also be placed under joint governance within a second binational zone.

A number of binational organisations should be established as part of this process:

- A water authority that coordinates and monitors shipping traffic.

- A company that operates and maintains the locks[wp].

- A company that rebuilds the Kakhovka Dam[wp] and maintains it together with the associated hydroelectric power plant.

- A company that operates the Energodar Nuclear Power Plant.

- A company that operates the Energodar Thermal Power Plant.

- The city of Energodar, on whose territory the Energodar Nuclear Power Plant and the Energodar Thermal Power Plant are located, should also become part of the binational zone, which in turn should be placed under binational administrative jurisdiction as a special zone.

Institutional Foundations

A federal constitution requires robust institutions. The design of a new constitutional framework must formally define the rights and responsibilities of federal entities. This design phase could be conducted via a constitutional assembly[wp] representing all regions, political groups, and civil society actors.

Successful federalization also calls for an internationally guaranteed transitional order to build trust, signal reliability, and ensure stability. One possible mechanism is a Trusteeship Council of neutral third‑party states that mediates between regional and central interests, monitors implementation, and supports governance processes.

In this context, membership in the Ukrainian state must accommodate diverse cultural identities—without imposing assimilation, yet with clear loyalty to the constitutional framework.

International Role and Connectivity

With clearly defined regional jurisdictions, Ukraine could pursue differentiated international partnerships—without overextending central control. Regions would have latitude to pursue economic and cultural links with neighboring countries or international organizations, while the national government could reframe its foreign policy on a stable, federally grounded basis.

Conclusion (Final Thought)

This is not a dry technocratic blueprint—it is an invitation to re-found political order in a space shaken by war, fragmentation, and loss of trust. Federalization is not an end, but a means: a framework in which regional identities, geopolitical realities, and state integrity are not contradictory, but interoperable components of a shared future.

It is realistic in diagnosis, hopeful in tone, and concrete in intention. It presents Ukraine as a plural political space—and proposes an order that bestows structure and stability upon that plurality.

- Ukraine could be a country where diverse regions, cultures, and worldviews do not exclude one another, but instead coexist institutionally. Achieving this requires courage in embracing difference—and trust in the power of peace‑oriented visions of political order.

Arguments

| Russische Medien und Politiker bezeichnen sie als "Anhänger einer Föderalisierung". Ihre ukrainischen Kollegen sprechen von "Separatisten". Die Rede ist von Tausenden Aktivisten, die seit Anfang April immer mehr Gebietsverwaltungen und Polizeizentralen in der Ostukraine besetzen[ext]. Viele von ihnen sind bewaffnet. Sie fordern ein Referendum über eine Föderalisierung der Ukraine, damit russischsprachige Regionen im Osten des Landes größere Vollmachten bekommen. Auch Russland will eine Föderalisierung der Ukraine. Sonst werde es keine Stabilität geben, so das Außenministerium in Moskau.

Verlangt wird eine grundlegende Verfassungsänderung, die es in der jüngsten Geschichte der Ukraine noch nie gegeben hat. Artikel 2 der Verfassung definiert die Ukraine als einen Einheitsstaat[wp]. Die ehemalige Sowjetrepublik ist aufgeteilt in 24 Gebiete (Oblast) und die Autonome Republik Krim[wp], die [zum Zeitpunkt des Artikels bereits die Sezession[wp] von der Ukraine vollzogen hatte]. Machtzentrale ist die Hauptstadt Kiew. Der Präsident, die Regierung und das Parlament entscheiden über alles: von Steuern bis hin zur Sprachpolitik. Das wollen die bewaffneten Aktivisten ändern. Neu sind diese Forderungen nicht. In den vergangenen Jahren hat sie nur kaum jemand ernstgenommen. [...] Eine Föderalisierung sollte Vadim Kolesnitschenko[wp] zufolge helfen, einen Zerfall des Staates zu verhindern. Noch früher hatte sich Viktor Medwedtschuk[wp] zu Wort gemeldet. "Die Föderalisierung ist die einzige und alternativlose Medizin gegen den Zerfall der Ukraine", schrieb der einst sehr einflussreiche ukrainische Politiker in seinem Blog bereits im Sommer 2012. Während der oppositionellen Proteste im Winter 2014 wiederholte er seine Forderung mehrmals. [...] Eine Föderalisierung der Ukraine könnte allein das Parlament beschließen. Interimspräsident Olexander Turtschinow[wp] erteilte den Forderungen aus Moskau eine klare Absage. Viele Politiker in Kiew befürchten, dass eine Föderalisierung zu einer Abspaltung der östlichen und südlichen Gebiete der Ukraine führen könnte. [...] Viele Menschen im Osten der Ukraine wollen aber, dass die Gebiete größere Vollmachten erhalten. |

| – Deutsche Welle[wp] on 15 April 2014[2] |

Quote: «Die von Russland geforderte Föderalisierung der Ukraine könnte zu einer Spaltung des Landes missbraucht werden.» - Positionen der EU und der Bundesregierung beim Genfer Ukraine-Treffen am 17. April 2014[3]

| WikiMANNia comment |

| In 2014, the argument against federalization was that it could lead to the secession of the eastern and southern regions of Ukraine. In 2024, it can be seen in retrospect that the retention of the centralist state organization, a rigorous Ukrainization[wp] carried out using coercive administrative measures and finally the brutal use of military force against the civilian population in the Donbas have led to the secession of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and four oblasts.

This disastrous result for the Ukrainian state should be reason enough to think again thoroughly and comprehensively about the federalization of the country. It is also interesting to read what Peter Scholl-Latour had to say about Ukraine, the USA, NATO and the CIA in 2006: |

Quote: «Man versetze sich in die Lage der russischen Patrioten: die NATO dehnt ihren militärischen Einfluss über die willfährige Ukraine bis zum Don[wp] aus. [...] (1:10) Kiev, die Hauptstadt der unabhängigen Republik Ukraine, galt stets als Mutter der russischen Steppe. Hier hatte sich nach der Bekehrung zur christlichen Orthodoxie vor 1000 Jahren die Geburt des russischen Staatswesens vollzogen. Die Rurikiden[wp]-Dynastie, Nachfolger des Kiever Großfürsten Wladimir[wp], herrschte ein halbes Jahrtausend bis zum Tod Iwans des Schrecklichen[wp] über das Moskowiter-Reich[wp], das sich den Titel "Drittes Rom" zugelegt hatte. Für Wladimir Putin[wp] ist der Abfall der Ukraine schwer erträglich.

(2:10) Jeder erinnert sich an die stürmische Begeisterung der Orange Revolution[wp] auf dem Maidan von Kiev, die dem Separatismus zum Sieg verhalf. Die Helden dieser nationalukrainischen Volkserhebung, an ihrer Spitze Präsident Wiktor Juschtschenko[wp], haben seitdem ihr Prestige eingebüsst. Seine Partei Nascha Ukrajina[wp] kam bei der jüngsten Parlamentswahl auf kümmerliche 13 Prozent.

(2:50) Vor allem hat sich inzwischen bestätigt, dass das Ausharren der revolutionären Masse in klirrender Kälte durch massive Unterstützung Amerikas und der Europäischen Union finanziert und ermöglicht wurde. Die Agenten der de:CIA, als NGO getarnt, haben in Kiev eine systematische Subversion[wp] des bestehenden Regimes betrieben. Ähnliches wurde ja auch in der benachbarten Republik Belarus[wp] versucht.

(3:22) Als wirkliche Siegerin der Unabhängigkeitsbewegung hat sich eine blonde energische Frau erwiesen, Julija Tymoschenko[wp]. Als Gasprinzessin wurde diese Oligarchin verspottet, als slawische Evita Peron[wp] wird sie bewundert. Der endgültige Kampf um die Ausübung der Macht ist in Kiev längst nicht entschieden.

(3:58) Zum politischen Bruch hat sich das religiöse Schisma gesellt. Unter dem selbsternannten Patriarchen Filaret[wp] hat sich die orthodoxe Kirche der Kiewer Rus[wp] aus der Bevormundung des Moskauer Patriarchats[wp] gelöst. Von Anfang an hatte sich der ukrainische Nationalismus auf die mit Rom unierten griechischkatholischen Gläubigen Ostgaliziens gestützt. Mit der Abspaltung Filarets wird die Autorität des Moskauer Kirchenfürsten Alexei[wp] auf die russischen Kernlande begrenzt.

(4:50) Gegengewicht und Kontrast zu Kiev bildet im Osten der Ukraine das Industrierevier Donbass mit der Stadt Donezk[wp], die einmal Stalino hieß. In dieser Landschaft von Stahlwerken und Zechen ist die Erinnerung an den Großen Vaterländischen Krieg[wp] längst nicht verblasst. Die Masse der Bevölkerung bekennt sich zur russischen Nationalität. Im Donbass wird das ganze Ausmaß der atlantischen und europäischen Bestrebung deutlich, die Grenzen Russlands in Richtung auf die Wolga und die asiatische Steppe zu verschieben.

(5:40) Nach dem Verlust der Ukraine sei Russland dazu verurteilt, ein überwiegend asiatisches Imperium zu werden, so verlocken bereits einige einflussreiche Ideologen in Washington und viele Europäer schließen sich diesem neuen Drang nach Osten der NATO an. [...]

(6:20) Welche strategischen Absichten, welche kapitalistischen Interessen, welch dilettantischer Leichtsinn verbergen sich hinter diesem Ritt nach Osten, zu dem die atlantische Allianz und in deren gehorsamen Gefolge die Europäische Union angetreten sind? Es geht in diesen Weiten, wo die Toten des Zweiten Weltkrieges noch nicht zur Ruhe kamen, nicht nur um die Ukraine, sondern um Weißrussland, Moldova und die kaukasischen Republiken. Sind sich Ölmagnat und Vizepräsident der USA Dick Cheney[wp] und leider auch der redliche Senator John McCain[wp] überhaupt bewusst, wie konsequent sie sich mit ihren Expansionsplänen den neuen Zaren Wladimir Putin zum Feind machen? Spüren die schadronierenden Europaabgeordneten nicht, dass sie in Restrussland ein nationalistisches Aufbäumen schüren. Oder soll am Ende zwischen Smolensk[wp] und Wladiwostok[wp] das Chaos entstehen?

(7:43) Im Donbass-Revier, in den Großstädten Donezk und Lugansk, hält sich die Empörung noch in Grenzen. [...]

(9:10) Wenn ukrainische Chöre in Donezk auftreten, wird deutlich, dass auch die Partei der Regionen[wp] nicht unbedingt den Anschluss an Moskau sucht, hingegen drängt sie auf die Gleichberechtigung der russischen Sprache neben dem ukrainischen, sowie auf eine weitgehende Autonomie von Kiev. Ganz unverhüllt erweisen sich in der ganzen Ukraine die Oligarchen, die Profiteure beim Ausverkauf der Perestroika[wp] als die wirklichen Potentaten. [...]» - Transcript of a ZDF documentary film from 2006[4]

| WikiMANNia comment |

| Peter Scholl-Latour was therefore already aware in 2006 that the USA was subverting Ukraine in violation of international law and wanted to admit it to NATO. The subversion of Ukraine by the USA was completed in 2014 with the Euromaidan coup[cp]. According to other sources, the infiltration by the USA began immediately after Ukraine's independence in 1991.

For rational and informed people, it was already clear in 2006 that the population of south-eastern Ukraine would hold on to its Russian identity, oppose Ukrainization and reject co-option[wp] by the US. In view of this, it was clear in 2006 what would follow in 2014 with the civil war and since 2022 with the proxy war against the Russian Federation. |

References

- ↑ A viable proposal is to divide the territory of Kherson Oblast along the Dnieper between the two countries, with the part to the right of the Dnieper remaining with Ukraine and within it being assigned to Mykolaiv Oblast[wp], while the part to the left of the Dnieper could be reorganised within the Russian Federation with Kakhovka[wp] as the new oblast capital and under the name of Kakhovka Oblast. As part of this territorial and political reorganisation between Russia and Ukraine, the Kinburn Peninsula[wp] was to be transferred from Mykolaiv Oblast to the new Kakhovka Oblast.

- ↑ Roman Goncharenko: Putins Plan "F" für die Ukraine, Deutsche Welle[wp] on 15 April 2014

- Teaser: Pro-russische Aktivisten in der Ostukraine fordern die Föderalisierung des Landes. Moskau argumentiert, größere Vollmachten für die Provinzen würden die Ukraine einen. Kiew befürchtet das Gegenteil.

- ↑ Schriftliche Frage: Positionen der EU und der Bundesregierung beim Genfer Ukraine-Treffen am 17. April 2014, bundestag.de

- ↑

Russland im Zangengriff - Putins Imperium zwischen Nato, China und Islam - Peter Scholl-Latour (ZDF) (February 4, 2006) (Size: 40:18 min.) (German)

Russland im Zangengriff - Putins Imperium zwischen Nato, China und Islam - Peter Scholl-Latour (ZDF) (February 4, 2006) (Size: 40:18 min.) (German)

- A 2006 documentary by PSL about Russia and its relationship with foreign countries.

Appendix

Detailed suggestions

- Budzhak Autonomous Oblast

- Chernivtsi Autonomous Oblast

- Autonomous Region of Galicia-Volhynia

- Autonomous Republic of Odesa

- Autonomous Republic of Transcarpathia

- Binational areas and organisations (Dnieper–Bug estuary[wp], lower reaches of the Dnieper[wp], Kakhovka Reservoir and the city of Energodar.)

- Kharkiv Oblast

- Mykolaiv Oblast

- Zaporizhzhia Oblast

Former Ukrainian territories

- Kakhovka Oblast (former Kherson Oblast[wp] without Beryslav Raion[wp] and the part of Kherson Raion[wp] on the right bank of the Dnieper)

- Melitopol Oblast (former Zaporizhzhia Oblast[wp] without Zaporizhzhia Raion[wp])

- Donetsk People's Republic (formerly Donetsk Oblast[wp])

- Lugansk People's Republic (formerly Lugansk Oblast[wp])

External links

- Michael Wolffsohn: Bundesrepublik Ukraine: Die Lösung für Frieden heißt Föderalismus, Der Freitag 12/2022

- Teaser: Meinung Um eine friedliche Lösung im Ukraine-Krieg zu finden, muss sich das Land zu einem föderalen Staat entwickeln.

- Marcel Röthig: Ukraine: "Autonomie für die Regionen", IPG-Journal on 13 March 2014

- Teaser: Nur eine Föderalisierung in zwei Stufen könnte die Krise entschärfen. Wenn man es richtig angeht.